Modern (Stone Age) Family

This, kids, is how cave people invented the prime time cartoon, and many of the tropes that go with it.

The Flintstones, "Flintstone Hillbillies"

OB: January 16, 1964, 7:30 p.m. EST, ABC

I was two days old when this episode first aired.

The Flintstones was filmed in color beginning with the very first episode, and broadcast that way beginning in season three...because what better way to stick it to CBS than to say, "Shoot, we here at ABC have been broadcasting in color since the stone age, unlike certain other networks."

Fans of The Simpsons know it as the "couch gag." It's the moment in that show's opening when the entire family rushes into the house at once, presumably to take their places on the couch in front of the TV, but something always comes up before that last step. And one week, the whole family stopped in their tracks to see Fred, Wilma and Pebbles Flintstone already sitting on their couch, watching their TV. Fred just looks at Homer, Marge, Bart, Lisa and Maggie, and shrugs.

That Simpsons couch gag is a nice tribute, because the Flintstones, and The Flintstones, really were there first. The original Flintstones opening even had Fred rushing home from work, jumping into his easy chair and turning on his TV. (That's probably where The Simpsons got the idea in the first place.) In so many ways, some intentional, some eerie, it appears the whole civilization of Springfield was built atop the ruins of the ancient civilization of Bedrock. And that goes for Quahog, Stoolbend, South Park and any other modern day animated TV town you could mention. (What can I say, Bedrock was huge...despite having a population of only 2,500 according to the first season opening credits.)

It all began during a period of transition, from "the Golden Age of Animation" to its so-called Dark Age. The (first) age of richly drawn work and Disney princesses was coming to an end; Bugs Bunny's legendary "What's Opera, Doc?" was a bug, not a feature, and Disney's "Sleeping Beauty" had actually bombed in theaters. There were two things going on at once that changed the way cartoons were drawn and marketed: the Hollywood studio system was in its death throes (and with it, the animated short as a common sight in theaters and drive-ins), and television was showing itself to have an insatiable appetite for quickly drawn, rushed to the airwaves animation. No longer did the norm involve taking two years for a Disney classic; you pretty much had to feed the beast and he was hungry, like, right now.

William Hanna and Joseph Barbera were queried by Screen Gems executives about a very simple idea: Hanna-Barbera had already produced syndicated cartoon series for television (The Ruff 'N' Reddy Show, Huckleberry Hound), but those were aimed at mostly children. So why not an animated series mostly for adults...like they did in the movies? Sure enough, anyone who's ever seen a Bugs Bunny cartoon knows clearly it had as much adult humor as could make it past the censors, as did the Tom and Jerry shorts Hanna-Barbera had done for MGM, since the cartoon shorts often preceded both children's and adult movies alike. (Plus they worked with Tex Avery, who seemed to enjoy screwing around with the censors as much as making cartoons of wolves with their eyeballs popping out.)

The conferences narrowed down what everyone wanted: a half hour sitcom, first of all, in prime time. They tossed around a number of ideas: the characters might be in ancient Rome, for instance (an idea H-B would try in 1972 with The Roman Holidays), or they might've been hillbillies. The "Eureka!" moment came when Hanna-Barbera storyboard editor Don Gordon suggested the characters all be cave people, and work with appliances, vehicles, etc. that were funny pre-historic versions of their modern-day counterparts. Gordon drew the first sketches, then they went to Ed Benedict, who had created a universe of cave people in the West for the 1955 Tex Avery MGM short, "The First Bad Man." Benedict drew on that inspiration as he developed who we would later know as Fred, Wilma, Barney and Betty.

Selling the idea wasn't easy. Joseph Barbera remembers going to numerous ad agencies and companies. He remembers the entire headquarters staff of Bristol Myers piling into a conference room to hear his 90 minute pitch (about Fred and Barney building a swimming pool), then later coming back for a command performance before the CEO. "...There were two agencies there, and neither one was going to let the other one know they were enjoying it," Joseph Barbera later recalled. "But I pitched it for eight straight weeks and nobody bought it." On what Barbera later claimed was going to be his last try before he'd decided to give up, he made that pitch to ABC...and they bought it in the room. At the time, ABC was a third place network with series aimed at various parts of the young demographic (77 Sunset Strip, Leave It to Beaver), basically the Fox of their day. And they were willing to take a chance on something that daring and new.

A brief pilot, "The Flagstones," was made for potential sponsors. However, the similarity in name to the Flagston family featured in the newspaper comic strip "Hi and Lois," resulted in a change to The Flintstones.

At first glance, in those early days, the bombastic but loving husband Fred, the wisecracking, level headed Wilma, and their neighbors, Betty and Barney (plus Fred's and Barney's membership in a lodge), seemed to all bear more than a passing resemblance to another classic TV foursome...the cast of The Honeymooners. Hanna and Barbera were actually split over whether that show inspired the characters, but both acknowledged being big fans of it. Jackie Gleason himself was said to have considered a lawsuit, and was even told by his lawyers it would be open and shut, but decided he didn't want the publicity of being known as "the man who killed Fred Flintstone."

Veteran character actor Alan Reed was cast as Fred Flintstone, and even looked a bit like him. Reed had been in numerous films such as "The Postman Always Rings Twice" and "The Desperate Hours," radio programs like Duffy's Tavern and The Life of Riley, and TV shows like The Donna Reed Show. When the script called for Fred to yell "Yahoo!" it was Reed who improvised the now-iconic "Yabba-Dabba-Doo!" in the audio booth. It was based on the phrase "A little dab'll do ya!" that his mother said a lot; that was also a slogan and jingle for Brylcreem. The greatest voice man of all time, Mel Blanc, added Barney Rubble to his thousand voices; Blanc was replaced briefly in 1961 as he recovered from a near-fatal car crash. Rounding out the cast were character actress Jean Vanderpyl as Wilma and Bea Benederet (The George Burns and Gracie Allen Show, Petticoat Junction) as Betty, then for the last two seasons by Gerry Johnson.

Then Hanna-Barbera landed two sponsors, one of which was Miles Laboratories, makers of Alka-Seltzer and One-a-Day Vitamins. And when I say this was an adult series, that means at least one adult sponsor...

...R.J. Reynolds, makers of Winston cigarettes.

To be fair, this was a controversial move at the time; we weren't that far gone in those days. Winston ultimately did drop their sponsorship in 1963, to be replaced by the more family-friendly Welch's jellies and juices and Skippy peanut butter.

The series premiered in September 1960 to big ratings, and a surprisingly bad, very rough review from Variety. Their critic called it a "pen and ink disaster" and portrayed Fred as an unlikable bully. It also wrongly predicted the show would be cancelled quickly and forgotten.

The show got decent, respectable ratings, finishing the 1960-61 season as the 18th most watched show on television. But it also started a huge marketing empire: comic books, Golden Books story books, toys. At one point Welch's jelly came in jars that could double as drinking glasses with character likenesses painted onto them, and a whole generation of us had Fred, Barney and the gang populating our kitchen cabinets.

The 1961-62 season premiere had Fred deciding he wanted to be a songwriter, and getting help from "Stoney Carmichael," actually voiced by none other than songwriting legend Hoagy Carmichael. To be sure, it wasn't the first time a celebrity likeness appeared in a cartoon. A 1920s "Felix the Cat" cartoon featured images of Charlie Chaplin and other stars of the day. Frank Sinatra's and Bing Crosby's actual voices could be heard singing in some cartoon shorts, and the cast of The Jack Benny Program even "appeared" as mice once in a Warner Brothers short.

What this did do, however, was pioneer the idea of "guest voices," celebrities who would voice their animated selves alongside series regulars. Sure enough, before the end of the series, we'd hear from "Stony Curtis,""Ann-Margrock,""Jimmy Darrock" and the "Beau Brummelstones," actually voiced by Tony Curtis, Ann-Margret, James Darren and the Beau Brummels. In one episode, Elizabeth Montgomery and Dick York even voiced animated versions of their Bewitched characters, Samantha and Darren Stevens. (According to York, they each got a TV set in lieu of payment.) This, of course, would pave the way for the incredibly stellar list of guest stars who later populated The Simpsons over the years.

There are plenty of other contemporary TV parodies as well, without the actual stars' voices. There's a variety show called "The Hollyrock Palace" (based on ABC's real variety show, The Hollywood Palace), and in a sendup of Bonanza, they meet the men of the Cartrock family. The episode that introduced Bamm-Bamm included a Perry Mason spoof, with an attorney named Bronto Berger representing the Rubbles and facing down the formidable Perry Masonry (who always defeats Berger in court) in a custody hearing.

By the time I was born, the show had evolved somewhat. In 1962 the show dropped its Simpsons-inspiring open and instrumental theme, with Fred rushing home to the TV, in favor of the more iconic trip to and from the drive-in, and added the now familiar "Meet the Flintstones" theme with full lyrics. (That theme debuted on a record album in 1961, and originally even had extra lyrics mentioning Dino and the Rubbles.)

Fred and Wilma made TV history as being among the few TV couples to be seen in bed together, the very first in animated TV. The previously childless Flintstones gave birth to Pebbles in February 1963; the following October, the Rubbles would adopt Bamm-Bamm. (In a very touching scene, the Rubbles had also wished upon a star for a child because they couldn't have any of their own. This made the show the first animated series to ever address infertility.) And the TV season in which I was born, kicked off with that memorable season premiere featuring "Ann-Margrock."

The week I was born, we get a possible glimpse at what the show almost became: a show about hillbillies.

It starts with a cold open, showing the Flintstones on a car trip crossing over from Tennestone, the "Wet State," to Arkanstone, the "Dry State." (The cold opens were usually scenes that were part of the plot, but wouldn't be seen in the actual episode since...well, we just saw it.)

It begins, strikingly enough, with a funeral for Zeke Flintstone, who fell out of a tree to his death at the age of 102 and was believed to be the last of the Flintstones. (You just don't see that many funerals in a medium whose characters are known to fall off cliffs and suffer a big bump on the head and a disgusted look...and sometimes, a brief accordion shape.) That's very sad news for the Hatrocks, the other half of a 90 year old feud, now distraught because they no longer had anyone to shoot at. They even suggested Zeke did it on purpose to deprive them of "the joy of shootin' at a Flintstone," and can't even take comfort in hunting wild animals because "Bears don't holler like a Flintstone when they're hit."

But they do take comfort in Granny's words, that the sheriff will find the rightful heirs of the Flintstone estate, San Cemente. Sure enough we see the sheriff dictating a letter to his secretary, who promptly chisels it and sends it via airmail.

Of course, the airmail gag is just one of the "animal inventions" featured in this episode, with others including a monkey running a soft drink machine and two elephants functioning as gas pumps...one of whom is named "Ethel." (But no dinosaurs are present at the gas station, perhaps so people won't assume this is a product placement for Sinclair gasoline.) These were a running feature on the show, the animals often complaining about their jobs as the airmail bird and soft drink machine monkey do.

Wilma calls Fred at work (prompting his dino-crane to complain about wives calling husbands at work, and telling the dino-crane next to him "I'm glad we work together!"). Fred decides to leave immediately with the family and the Rubbles, because "The sooner we leave, the sooner I get what's coming to me."

First Fred taunts the Hatrocks, only to get beaned on the head by a rock thrown from one of the guns. Then Barney tries to reason with them, asking them not to shoot the Rubbles because they're not Flintstones. They get the "any friend of the Flintstones is an enemy of the Hatrocks!" line and gunfire.

This, kids, is how cave people invented the prime time cartoon, and many of the tropes that go with it.

The Flintstones, "Flintstone Hillbillies"

OB: January 16, 1964, 7:30 p.m. EST, ABC

I was two days old when this episode first aired.

The Flintstones was filmed in color beginning with the very first episode, and broadcast that way beginning in season three...because what better way to stick it to CBS than to say, "Shoot, we here at ABC have been broadcasting in color since the stone age, unlike certain other networks."

Fans of The Simpsons know it as the "couch gag." It's the moment in that show's opening when the entire family rushes into the house at once, presumably to take their places on the couch in front of the TV, but something always comes up before that last step. And one week, the whole family stopped in their tracks to see Fred, Wilma and Pebbles Flintstone already sitting on their couch, watching their TV. Fred just looks at Homer, Marge, Bart, Lisa and Maggie, and shrugs.

That Simpsons couch gag is a nice tribute, because the Flintstones, and The Flintstones, really were there first. The original Flintstones opening even had Fred rushing home from work, jumping into his easy chair and turning on his TV. (That's probably where The Simpsons got the idea in the first place.) In so many ways, some intentional, some eerie, it appears the whole civilization of Springfield was built atop the ruins of the ancient civilization of Bedrock. And that goes for Quahog, Stoolbend, South Park and any other modern day animated TV town you could mention. (What can I say, Bedrock was huge...despite having a population of only 2,500 according to the first season opening credits.)

It all began during a period of transition, from "the Golden Age of Animation" to its so-called Dark Age. The (first) age of richly drawn work and Disney princesses was coming to an end; Bugs Bunny's legendary "What's Opera, Doc?" was a bug, not a feature, and Disney's "Sleeping Beauty" had actually bombed in theaters. There were two things going on at once that changed the way cartoons were drawn and marketed: the Hollywood studio system was in its death throes (and with it, the animated short as a common sight in theaters and drive-ins), and television was showing itself to have an insatiable appetite for quickly drawn, rushed to the airwaves animation. No longer did the norm involve taking two years for a Disney classic; you pretty much had to feed the beast and he was hungry, like, right now.

William Hanna and Joseph Barbera were queried by Screen Gems executives about a very simple idea: Hanna-Barbera had already produced syndicated cartoon series for television (The Ruff 'N' Reddy Show, Huckleberry Hound), but those were aimed at mostly children. So why not an animated series mostly for adults...like they did in the movies? Sure enough, anyone who's ever seen a Bugs Bunny cartoon knows clearly it had as much adult humor as could make it past the censors, as did the Tom and Jerry shorts Hanna-Barbera had done for MGM, since the cartoon shorts often preceded both children's and adult movies alike. (Plus they worked with Tex Avery, who seemed to enjoy screwing around with the censors as much as making cartoons of wolves with their eyeballs popping out.)

The conferences narrowed down what everyone wanted: a half hour sitcom, first of all, in prime time. They tossed around a number of ideas: the characters might be in ancient Rome, for instance (an idea H-B would try in 1972 with The Roman Holidays), or they might've been hillbillies. The "Eureka!" moment came when Hanna-Barbera storyboard editor Don Gordon suggested the characters all be cave people, and work with appliances, vehicles, etc. that were funny pre-historic versions of their modern-day counterparts. Gordon drew the first sketches, then they went to Ed Benedict, who had created a universe of cave people in the West for the 1955 Tex Avery MGM short, "The First Bad Man." Benedict drew on that inspiration as he developed who we would later know as Fred, Wilma, Barney and Betty.

Selling the idea wasn't easy. Joseph Barbera remembers going to numerous ad agencies and companies. He remembers the entire headquarters staff of Bristol Myers piling into a conference room to hear his 90 minute pitch (about Fred and Barney building a swimming pool), then later coming back for a command performance before the CEO. "...There were two agencies there, and neither one was going to let the other one know they were enjoying it," Joseph Barbera later recalled. "But I pitched it for eight straight weeks and nobody bought it." On what Barbera later claimed was going to be his last try before he'd decided to give up, he made that pitch to ABC...and they bought it in the room. At the time, ABC was a third place network with series aimed at various parts of the young demographic (77 Sunset Strip, Leave It to Beaver), basically the Fox of their day. And they were willing to take a chance on something that daring and new.

A brief pilot, "The Flagstones," was made for potential sponsors. However, the similarity in name to the Flagston family featured in the newspaper comic strip "Hi and Lois," resulted in a change to The Flintstones.

At first glance, in those early days, the bombastic but loving husband Fred, the wisecracking, level headed Wilma, and their neighbors, Betty and Barney (plus Fred's and Barney's membership in a lodge), seemed to all bear more than a passing resemblance to another classic TV foursome...the cast of The Honeymooners. Hanna and Barbera were actually split over whether that show inspired the characters, but both acknowledged being big fans of it. Jackie Gleason himself was said to have considered a lawsuit, and was even told by his lawyers it would be open and shut, but decided he didn't want the publicity of being known as "the man who killed Fred Flintstone."

Veteran character actor Alan Reed was cast as Fred Flintstone, and even looked a bit like him. Reed had been in numerous films such as "The Postman Always Rings Twice" and "The Desperate Hours," radio programs like Duffy's Tavern and The Life of Riley, and TV shows like The Donna Reed Show. When the script called for Fred to yell "Yahoo!" it was Reed who improvised the now-iconic "Yabba-Dabba-Doo!" in the audio booth. It was based on the phrase "A little dab'll do ya!" that his mother said a lot; that was also a slogan and jingle for Brylcreem. The greatest voice man of all time, Mel Blanc, added Barney Rubble to his thousand voices; Blanc was replaced briefly in 1961 as he recovered from a near-fatal car crash. Rounding out the cast were character actress Jean Vanderpyl as Wilma and Bea Benederet (The George Burns and Gracie Allen Show, Petticoat Junction) as Betty, then for the last two seasons by Gerry Johnson.

Then Hanna-Barbera landed two sponsors, one of which was Miles Laboratories, makers of Alka-Seltzer and One-a-Day Vitamins. And when I say this was an adult series, that means at least one adult sponsor...

...R.J. Reynolds, makers of Winston cigarettes.

To be fair, this was a controversial move at the time; we weren't that far gone in those days. Winston ultimately did drop their sponsorship in 1963, to be replaced by the more family-friendly Welch's jellies and juices and Skippy peanut butter.

The series premiered in September 1960 to big ratings, and a surprisingly bad, very rough review from Variety. Their critic called it a "pen and ink disaster" and portrayed Fred as an unlikable bully. It also wrongly predicted the show would be cancelled quickly and forgotten.

The show got decent, respectable ratings, finishing the 1960-61 season as the 18th most watched show on television. But it also started a huge marketing empire: comic books, Golden Books story books, toys. At one point Welch's jelly came in jars that could double as drinking glasses with character likenesses painted onto them, and a whole generation of us had Fred, Barney and the gang populating our kitchen cabinets.

The 1961-62 season premiere had Fred deciding he wanted to be a songwriter, and getting help from "Stoney Carmichael," actually voiced by none other than songwriting legend Hoagy Carmichael. To be sure, it wasn't the first time a celebrity likeness appeared in a cartoon. A 1920s "Felix the Cat" cartoon featured images of Charlie Chaplin and other stars of the day. Frank Sinatra's and Bing Crosby's actual voices could be heard singing in some cartoon shorts, and the cast of The Jack Benny Program even "appeared" as mice once in a Warner Brothers short.

What this did do, however, was pioneer the idea of "guest voices," celebrities who would voice their animated selves alongside series regulars. Sure enough, before the end of the series, we'd hear from "Stony Curtis,""Ann-Margrock,""Jimmy Darrock" and the "Beau Brummelstones," actually voiced by Tony Curtis, Ann-Margret, James Darren and the Beau Brummels. In one episode, Elizabeth Montgomery and Dick York even voiced animated versions of their Bewitched characters, Samantha and Darren Stevens. (According to York, they each got a TV set in lieu of payment.) This, of course, would pave the way for the incredibly stellar list of guest stars who later populated The Simpsons over the years.

There are plenty of other contemporary TV parodies as well, without the actual stars' voices. There's a variety show called "The Hollyrock Palace" (based on ABC's real variety show, The Hollywood Palace), and in a sendup of Bonanza, they meet the men of the Cartrock family. The episode that introduced Bamm-Bamm included a Perry Mason spoof, with an attorney named Bronto Berger representing the Rubbles and facing down the formidable Perry Masonry (who always defeats Berger in court) in a custody hearing.

By the time I was born, the show had evolved somewhat. In 1962 the show dropped its Simpsons-inspiring open and instrumental theme, with Fred rushing home to the TV, in favor of the more iconic trip to and from the drive-in, and added the now familiar "Meet the Flintstones" theme with full lyrics. (That theme debuted on a record album in 1961, and originally even had extra lyrics mentioning Dino and the Rubbles.)

Fred and Wilma made TV history as being among the few TV couples to be seen in bed together, the very first in animated TV. The previously childless Flintstones gave birth to Pebbles in February 1963; the following October, the Rubbles would adopt Bamm-Bamm. (In a very touching scene, the Rubbles had also wished upon a star for a child because they couldn't have any of their own. This made the show the first animated series to ever address infertility.) And the TV season in which I was born, kicked off with that memorable season premiere featuring "Ann-Margrock."

The week I was born, we get a possible glimpse at what the show almost became: a show about hillbillies.

It starts with a cold open, showing the Flintstones on a car trip crossing over from Tennestone, the "Wet State," to Arkanstone, the "Dry State." (The cold opens were usually scenes that were part of the plot, but wouldn't be seen in the actual episode since...well, we just saw it.)

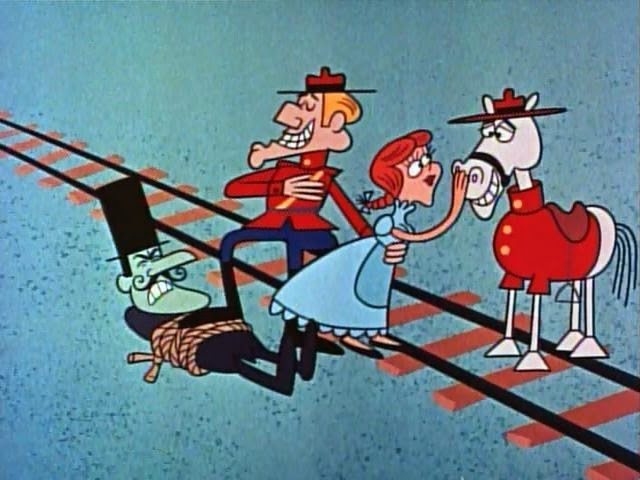

It begins, strikingly enough, with a funeral for Zeke Flintstone, who fell out of a tree to his death at the age of 102 and was believed to be the last of the Flintstones. (You just don't see that many funerals in a medium whose characters are known to fall off cliffs and suffer a big bump on the head and a disgusted look...and sometimes, a brief accordion shape.) That's very sad news for the Hatrocks, the other half of a 90 year old feud, now distraught because they no longer had anyone to shoot at. They even suggested Zeke did it on purpose to deprive them of "the joy of shootin' at a Flintstone," and can't even take comfort in hunting wild animals because "Bears don't holler like a Flintstone when they're hit."

But they do take comfort in Granny's words, that the sheriff will find the rightful heirs of the Flintstone estate, San Cemente. Sure enough we see the sheriff dictating a letter to his secretary, who promptly chisels it and sends it via airmail.

Of course, the airmail gag is just one of the "animal inventions" featured in this episode, with others including a monkey running a soft drink machine and two elephants functioning as gas pumps...one of whom is named "Ethel." (But no dinosaurs are present at the gas station, perhaps so people won't assume this is a product placement for Sinclair gasoline.) These were a running feature on the show, the animals often complaining about their jobs as the airmail bird and soft drink machine monkey do.

Wilma calls Fred at work (prompting his dino-crane to complain about wives calling husbands at work, and telling the dino-crane next to him "I'm glad we work together!"). Fred decides to leave immediately with the family and the Rubbles, because "The sooner we leave, the sooner I get what's coming to me."

When they get to a filling station in Arkanstone, Wilma says Pebbles wants grape juice, and Barney decides to get some for himself and Fred. And yes, this is an obvious product placement for the show's sponsor, Welch's.

The service station attendant (with the unmistakable voice of Howard Morris, sounding just like the Ernest T. Bass character he'll play just two weeks later on The Andy Griffith Show; Morris did about six different voices in this one episode) hears that they're named Flintstone, and warns them away from the feuding Hatrocks. Fred doesn't take this seriously and tries to swear Barney to secrecy. So they start up the hill to San Cemente, as the attendant calls the Hatrocks.

Wilma: I wonder what kind of reception we'll get from our neighbors?

Betty: As the last of the Flintstones, you'll probably get a 21 gun salute!

Sure enough, the gunfire starts pretty soon, and the Flintstones and Rubbles have to take shelter inside San Cemente.

First Fred taunts the Hatrocks, only to get beaned on the head by a rock thrown from one of the guns. Then Barney tries to reason with them, asking them not to shoot the Rubbles because they're not Flintstones. They get the "any friend of the Flintstones is an enemy of the Hatrocks!" line and gunfire.

Finally, Wilma, Pebbles and Dino invent automatic weaponry and throw numerous stones at the Hatrocks at once. Eventually Granny and Cruella Hatrock bring over a pie for Wilma and Betty, a possum pie with a live, smartalec possum inside. The women describe how the feud began, with a Flintstone ancestor insulting a painting of a Hatrock ancestor. "I don't know what he got for paintin' that but he shoulda gotten life!" the older Flintstone had reportedly said about the artist.

That's when the Flintstones notice Pebbles is missing (Bamm-Bamm didn't make the trip, they left him with a sitter) and the Hatrocks notice Slab, their baby son, is missing too. The two had actually crawled across the meadow onto a log that went downstream near a waterfall; Fred, hanging upside down from a tree, rescues them. Wilma and Cruella talk about wanting to spank their children, but see them hugging and suggest we could all learn from them. So the Hatrocks, in the Flintstones' debt, call off the feud.

At the Hatrocks' party, Fred sees that same painting of the Hatrock ancestor "by a famous artist" (it looks like a stone age, bucktoothed parody of Whistler's Mother) and Fred responds with the exact same insult of generations before ("...shoulda gotten life!"). The feud is back on and we last week the Hatrocks chasing on foot as the Flintstones and Rubbles speed away in their car. "This is the last they're going to see of the last of the Flintstones!" says Fred.

While the episode was likely inspired by the premiere of The Beverly Hillbillies one season earlier, it doesn't have the same family dynamic (family members who match up to Granny, Jethro, Elly May, etc.). This was likely something along the lines of the original version of The Flintstones before it was decided they'd be cave people. It also seems to fuel the inspiration of another future Hanna-Barbera creation, the "Hillbilly Bears" segment of The Atom Ant Show and later, The Banana Splits Adventure Hour. ("The Hillbilly Bears" also borrows more heavily from The Beverly Hillbillies).

Even though The Flintstones wasn't actually the first prime time cartoon (The Gerald McBoing-Boing Show had that distinction during the short-lived show's reruns on ABC in 1957), and wasn't even the only one to premiere in 1960 (it did so alongside ABC's The Bugs Bunny Show), it was the first with stories and characters specifically created for prime time and to appeal to adults. It was the first to air in a sitcom format, complete even with a laughtrack (a move that would populate Saturday morning cartoons for years), and the model for so many other similar shows. It set off a brief trend in prime time animation, even if the successor shows didn't quite fare as well. The Alvin Show and The Jetsons would last one season each; The Bullwinkle Show, joining NBC's prime time lineup for one season in 1961-62, would finish out its run on Saturday mornings without losing its razor-sharp, sophisticated humor.

Still, The Flintstones showed prime time animation would bring in viewers and did have one long term impact: the animated holiday special. "Mister Magoo's Christmas Carol" was the first in 1962, followed by "Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer" in 1964. Beginning in 1965, the "Peanuts" specials began to appear, first at Christmas, then at Halloween. The Flintstones and the Rubbles would even appear in one of their own in the late 1970s, complete with a talking baby Pebbles and a Santa Claus who used a CB radio. And like the original series, it showed the citizens of Bedrock actually celebrated Christmas millions of years before the birth of Christ.

Even though I laughed out loud at "Flintstone Hillbillies" (known in some episode guides as "Bedrock Hillbilllies"), the era in which I was born was actually when the show was in decline. The previous season was its last in the Top 30, with many fans considering the post-Pebbles and Bamm-Bamm scripts a bit juvenile. (The episode in which Pebbles was born, however, had a very surprising amount of grown-up farce based on mistaken identity, etc. It's a laugh-out-loud hoot.) The show's final, "jump the shark" season included a plot gimmick that's since been ridiculed and satirized as much as the "wraparound background" we always saw during chase scenes: the introduction of the floating little green man, Gazoo. He was visible only to Fred and Barney for some reason (and later to Pebbles and Bamm-Bamm), and voiced by Harvey Korman. He was supposed to function as something of a guardian angel for Fred, but wasn't able to save him from being cancelled by ABC in 1966.

Even though The Flintstones wasn't actually the first prime time cartoon (The Gerald McBoing-Boing Show had that distinction during the short-lived show's reruns on ABC in 1957), and wasn't even the only one to premiere in 1960 (it did so alongside ABC's The Bugs Bunny Show), it was the first with stories and characters specifically created for prime time and to appeal to adults. It was the first to air in a sitcom format, complete even with a laughtrack (a move that would populate Saturday morning cartoons for years), and the model for so many other similar shows. It set off a brief trend in prime time animation, even if the successor shows didn't quite fare as well. The Alvin Show and The Jetsons would last one season each; The Bullwinkle Show, joining NBC's prime time lineup for one season in 1961-62, would finish out its run on Saturday mornings without losing its razor-sharp, sophisticated humor.

Still, The Flintstones showed prime time animation would bring in viewers and did have one long term impact: the animated holiday special. "Mister Magoo's Christmas Carol" was the first in 1962, followed by "Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer" in 1964. Beginning in 1965, the "Peanuts" specials began to appear, first at Christmas, then at Halloween. The Flintstones and the Rubbles would even appear in one of their own in the late 1970s, complete with a talking baby Pebbles and a Santa Claus who used a CB radio. And like the original series, it showed the citizens of Bedrock actually celebrated Christmas millions of years before the birth of Christ.

Even though I laughed out loud at "Flintstone Hillbillies" (known in some episode guides as "Bedrock Hillbilllies"), the era in which I was born was actually when the show was in decline. The previous season was its last in the Top 30, with many fans considering the post-Pebbles and Bamm-Bamm scripts a bit juvenile. (The episode in which Pebbles was born, however, had a very surprising amount of grown-up farce based on mistaken identity, etc. It's a laugh-out-loud hoot.) The show's final, "jump the shark" season included a plot gimmick that's since been ridiculed and satirized as much as the "wraparound background" we always saw during chase scenes: the introduction of the floating little green man, Gazoo. He was visible only to Fred and Barney for some reason (and later to Pebbles and Bamm-Bamm), and voiced by Harvey Korman. He was supposed to function as something of a guardian angel for Fred, but wasn't able to save him from being cancelled by ABC in 1966.

But as the Hatrocks found out...you can't truly kill a Flintstone. Their vast empire of merchandising and spinoffs was just getting started. NBC picked up the reruns for Saturday mornings in the late 1960s before it went into syndication in 1971. Miles Laboratories, impressed with the Bedrock gang's track record of selling vitamins, gave them their own line of them, Flintstones Chewables, shaped like most of the characters. And whenever you see new animation featuring the Flintstones characters today, there's a 90% chance it'll be because they're in a commercial selling Post Fruity Pebbles and Cocoa Pebbles, two cereals introduced in the 1970s and still going strong.

What was supposed to be an epic multi-part season premiere for the 1966-67 season instead became their first theatrical film, the spy caper "A Man Called Flintstone." The Flintstones characters began their Saturday morning resurgence when a now-teenaged Pebbles and Bamm-Bamm got their own Saturday morning show in the early 1970s. Other series and movies followed, including the two 1990s live-action movies featuring John Goodman as Fred and Rick Moranis as Barney, not to mention Rosie O'Donnell in a memorable role as Betty Rubble, right down to Bea Benaderet's laugh.

Just the reruns are an empire of their own: they've been a longstanding flagship show of the Turner family, even back to the days when Ted Turner ran a single independent Atlanta station, WTCG, Channel 17. Fred and Barney stayed alongside the Turner empire as it grew to Superstation TBS and later changed hands, then as they were "reassigned" to the fledgling Cartoon Network and later to Boomerang.

CN, in fact, developed an entire "Adult Swim" lineup, one of the many, many heirs to the prime time animation estate left by Fred Flintstone. Prime time animation, in fact, made a major comeback when The Simpsons followed their appearances on The Tracey Ullman Show to their own, long-running spinoff with an empire of its own. And that led to an endless parade of shows that also owed their roots and formats to the Flintstones: King of the Hill, South Park, Family Guy, American Dad, The Cleveland Show, Bob's Burgers, Futurama...and still too many others to name (I haven't even gotten to the edgy serious animation like Batman: the Animated Series). With them all came merchandising empires. We may have almost forgotten about King of the Hill already, but if The Simpsons ever called it quits, it would likely follow the Flintstones example with a permanent marketing empire.

If Tom and Jerry laid the cornerstone for Hanna-Barbera while Huckleberry Hound and Yogi Bear cleared the land, it was The Flintstones which truly laid the foundation and even built most of the first floor of that empire. And that goes for all prime time, and by extension, serious TV animation that's come along since. It all goes to show, even though it has its roots in a "dark period" of animation, one simple little idea ("a show about cave people") coupled with a simple but revolutionary idea ("Let's put it in prime time, like Ozzie & Harriet and Lawrence Welk") could spark an entire, billion-dollar industry. Like those smartalec animals that powered the prehistoric time clocks, record players, etc. implied very heavily...Bedrock was a city millions of years ahead of its time.

Availability: the entire series is available on DVD and the first four seasons are available on Amazon.

Next time on this channel: Perry Mason.

What was supposed to be an epic multi-part season premiere for the 1966-67 season instead became their first theatrical film, the spy caper "A Man Called Flintstone." The Flintstones characters began their Saturday morning resurgence when a now-teenaged Pebbles and Bamm-Bamm got their own Saturday morning show in the early 1970s. Other series and movies followed, including the two 1990s live-action movies featuring John Goodman as Fred and Rick Moranis as Barney, not to mention Rosie O'Donnell in a memorable role as Betty Rubble, right down to Bea Benaderet's laugh.

Just the reruns are an empire of their own: they've been a longstanding flagship show of the Turner family, even back to the days when Ted Turner ran a single independent Atlanta station, WTCG, Channel 17. Fred and Barney stayed alongside the Turner empire as it grew to Superstation TBS and later changed hands, then as they were "reassigned" to the fledgling Cartoon Network and later to Boomerang.

CN, in fact, developed an entire "Adult Swim" lineup, one of the many, many heirs to the prime time animation estate left by Fred Flintstone. Prime time animation, in fact, made a major comeback when The Simpsons followed their appearances on The Tracey Ullman Show to their own, long-running spinoff with an empire of its own. And that led to an endless parade of shows that also owed their roots and formats to the Flintstones: King of the Hill, South Park, Family Guy, American Dad, The Cleveland Show, Bob's Burgers, Futurama...and still too many others to name (I haven't even gotten to the edgy serious animation like Batman: the Animated Series). With them all came merchandising empires. We may have almost forgotten about King of the Hill already, but if The Simpsons ever called it quits, it would likely follow the Flintstones example with a permanent marketing empire.

If Tom and Jerry laid the cornerstone for Hanna-Barbera while Huckleberry Hound and Yogi Bear cleared the land, it was The Flintstones which truly laid the foundation and even built most of the first floor of that empire. And that goes for all prime time, and by extension, serious TV animation that's come along since. It all goes to show, even though it has its roots in a "dark period" of animation, one simple little idea ("a show about cave people") coupled with a simple but revolutionary idea ("Let's put it in prime time, like Ozzie & Harriet and Lawrence Welk") could spark an entire, billion-dollar industry. Like those smartalec animals that powered the prehistoric time clocks, record players, etc. implied very heavily...Bedrock was a city millions of years ahead of its time.

Availability: the entire series is available on DVD and the first four seasons are available on Amazon.

Next time on this channel: Perry Mason.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)